3rd week: being and doing

Before moving on to this week’s subject matter, take a moment to look back at last week’s themes and exercises.

How did it feel to practise observing the time travel of your thoughts? Where did you find your mind spending the most time?

Did you practise mindfulness in everyday life? If you did, think about how carrying out an everyday task consciously differed from your usual way of doing it.

If you did not do the exercise, think about what prevented it. Did you remember to practise? If not, how could you ensure that you will remember going forward? Or did the exercise perhaps arouse some thoughts or emotions in you that made you refrain from doing it? How could you approach these “internal obstacles” in the future?

Finally, think about how the time travel of your thoughts and mindfulness in everyday life could be connected to your mood. Write down your thoughts.

Next, you can move on to this week’s themes. But before you do, do the three-minute meditation exercise from the previous weeks.

3-minute meditation

Modes of mind

Last week, we examined how the mind does many things automatically or by itself. It thinks, worries, reminisces and anticipates without our conscious decision to do so. When our mind is on autopilot like this, it is in a mode of doing. Conversely, when we are consciously present, our mind is in a mode of being. The next video provides more information about the modes of the mind and how they are related to depression.

Modes of mind and depression

Contemplate: do you have experiences of being able to just be in your everyday life?

Contemplate: do you have experiences of constantly thinking about something? Do you have experiences of your mind solving problems, reminiscing about unpleasant experiences or worrying about the future as if by itself?

We need both the mode of doing and the mode of being. The mode of doing helps us achieve goals and act efficiently. The fact that the human mind is capable of learning from the past and imagining things has facilitated the existence of science, stories and many other creations of humanity.

By contrast, the mode of being makes it possible for us to recover from the mode of doing, calm down and enjoy life. In the mode of being, our mind gets a moment of rest from constant thinking. This enables us to connect with other people, nature, art and ourselves.

Unpleasant emotions and melancholy are a natural reaction to certain situations, and they often pass by themselves if we allow them to. But when feeling melancholy, sad or otherwise negative, the majority of people feel that they have to do something about it. They have a need to understand why, cheer up, focus on other things, analyse, think positively – the list goes on and on. The mind starts to work to rid itself of this negative state. In other words, it switches to the mode of doing.

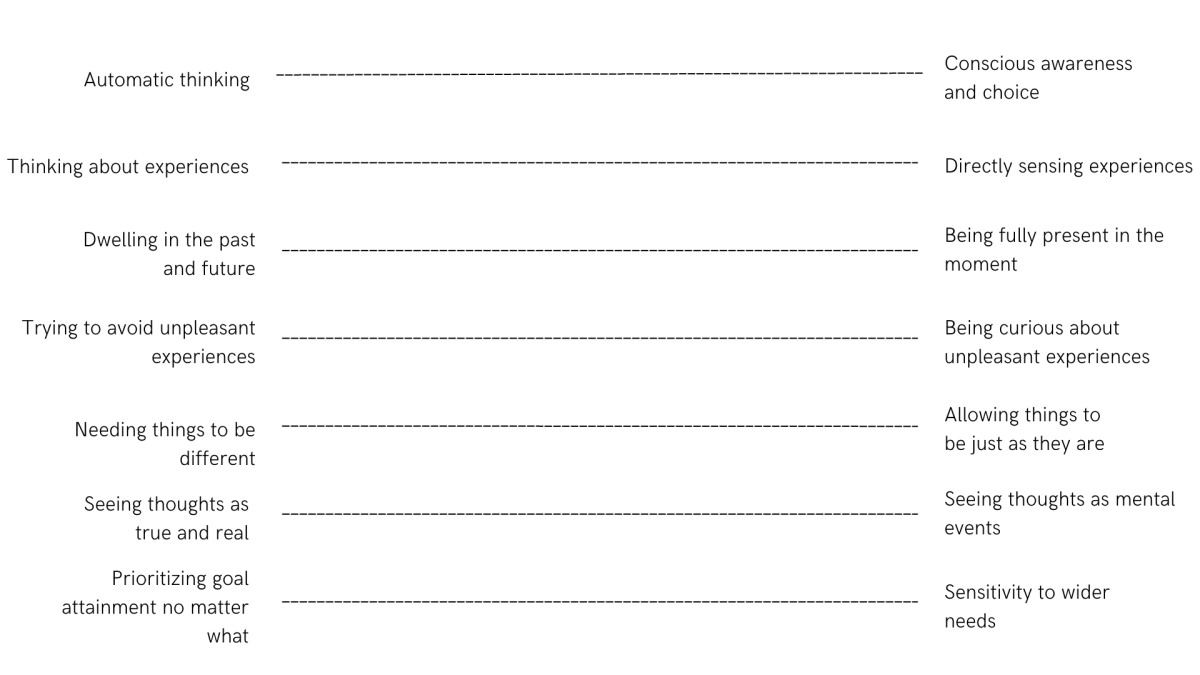

The mode of doing is characterised by the following:

- Our thinking is automatic.

- Our attention focuses on thoughts and ideas – not what we are observing or sensing here and now.

- Our thoughts focus on the past and the future.

- Avoiding unpleasant experiences is key.

- We have a need for things to be different.

- We take our thoughts as facts.

- Our mind focuses on a goal, even if it impacts us negatively – e.g. makes us have a severe or unfriendly attitude towards ourselves or others, or exhausts us completely.

Contemplate: what is your thinking like in the mode of doing? In what kinds of situations do you find that your mind operates as described above? Write down your thoughts.

The mode of doing is especially useful in situations in which we have to solve a concrete problem or come up with a plan for reaching a goal. Our mind then focuses on three things:

- what the situation is like now,

- what our own goal or wish is,

- what we want to avoid.

Problems arise from the fact that our mind does not automatically make a distinction between what kinds of things the mode of doing can and cannot be applied to. When our mind processes depression in the mode of doing, it processes the same aforementioned things actively and by itself:

- “I am depressed.”

- “I wish I was happier.”

- “I do not want to feel this bad.”

Anyone’s mood is likely to decline if they think along these lines.

Sometimes our mind can stop thinking about depression altogether in order to avoid difficult emotions arising from it. Outside, this may appear as being overly positive, and by contrast, we may feel numb or empty.

Other times, our mind may try even harder to solve a problem, switching to a mode of compulsive doing. In that mode, we feel like we have to get what we want or get rid of what we do not want. We are unable to stop thinking about it. One example of such compulsive thinking is rumination.

Contemplate: is there something familiar to you about the mode of compulsive doing? Does you mind sometimes keep mulling over problems and unpleasant experiences over and over again so that you are unable to stop thinking about them? How does this affect your mood? Write down your thoughts.

An alternative to the mode of doing is the mode of being. You have actually already tried it in different exercises. The mode of being is very natural in children, but many have forgotten about it in their adulthood. Fortunately, we can learn to return to it.

The mode of being is characterised by the following:

- Conscious presence and choices.

- Our attention focuses directly on what we experience – not our thoughts about it.

- We are focusing on the present moment.

- We have a curious attitude towards all of our experiences – including those that we avoid in the mode of doing.

- All of our experiences are allowed to be whatever they are.

- Our thoughts are like our mind’s way of sensing the world. They come and go and we do not see them as absolute truths.

- We see our goals as part of a bigger picture in which our wellbeing and that of others is important as well.

Actually, the mode of being is very similar to mindfulness – you could even say that they are one and the same. By practising mindfulness, we can learn to notice when our mind is starting to go into overdrive as it tries to think away difficult emotions. We can learn to let these emotions be, whereby they are allowed to go at their own pace.

In the next video, experts by experience think about how mindfulness feels and what practising it has brought to their lives.

What does mindfulness feel like?

In this programme, you have already learned about what automatic thinking is, examined the time travel of your thoughts and practised refocusing your attention from your thoughts directly onto your experience. In essence, you have already practised switching from doing to being.

Next, do an exercise in which you examine the same familiar thing – your feet – through the modes of doing and being.

Two ways of knowing

Contemplate: how did thinking about your feet differ from experiencing your feet? Was either way more familiar to you – do you think about things in your mind or experience them directly?

Balance between doing and being

Contemplate: how is the balance between the modes of doing and being in your life? Think about where you would place yourself on the lines below.

Exercises for the week

This week, practise switching from the mode of doing to the mode of being. Try to notice when you are thinking about something in your mind and see if you could sense and experience that thing directly. For example, if you notice that you are thinking about the food that you are eating, try to shift your focus onto how the food smells, tastes and feels in your mouth.

Try also to stop every day at least once to observe what the experience of your feet is like at that moment. You can use the ‘Two ways to know’ recording as an aid or do the exercise without it.

Like last week, be sure to also continue practising mindfulness in everyday life. Try to keep doing the everyday task that you chose last week consciously this week as well. Additionally, choose another mundane task and start practising doing it consciously.