2. Regulating moods and emotions

We are all born with emotions, but not with emotional regulation skills. We learn those skills in our childhood and youth in particular. Challenges with emotional regulation are the most significant set of symptoms associated with emotional instability.

A young child needs plenty of help from adults to identify and verbalise their emotions, as well as for controlling their own actions, and with age, they will learn to regulate their emotions more independently. These skills are developed particularly in situations in which emotions run high. The foundation for emotional regulation skills is laid in childhood, but these skills can also be learned in adulthood.

The video below provides more information on emotional and mood regulation.

Mood and emotions

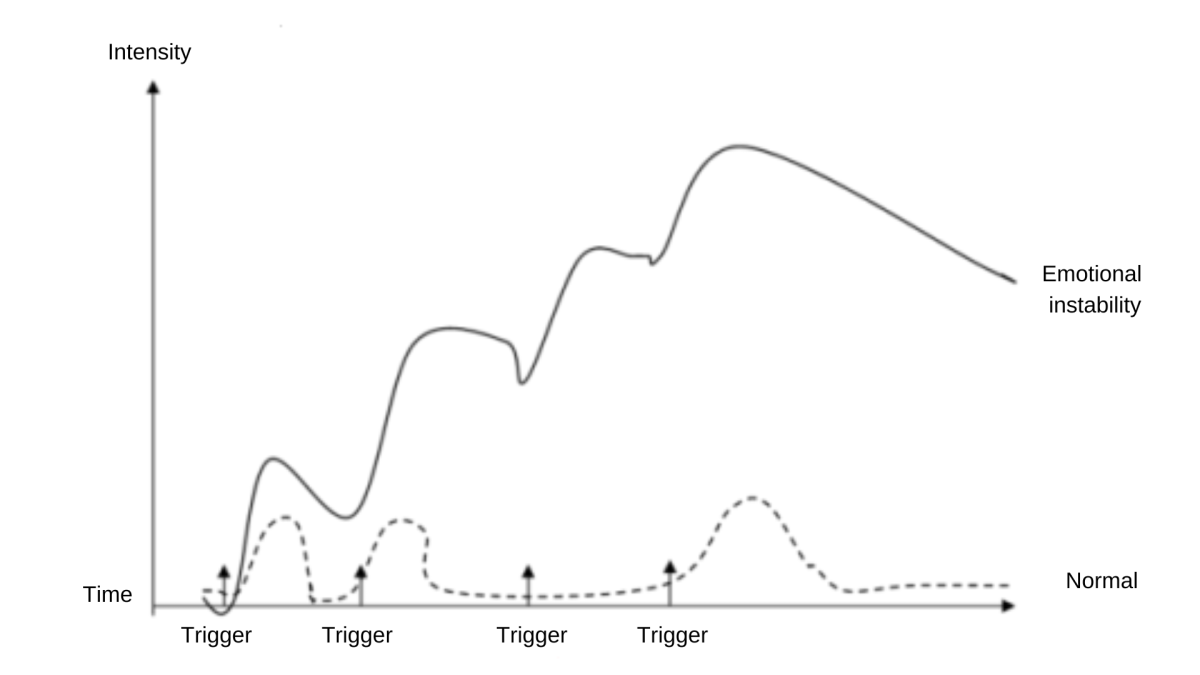

Emotional instability involves a very high sensitivity to emotional stimuli. Even something small can quickly stir up very strong emotions, and the emotional reaction is also slow to dissipate.

Whereas another person’s emotional reaction may have already evened out by the time the next emotionally triggering thing happens, a person with emotional instability may still be ‘running hot.’ In that case, the person will react to the new thing ‘too’ strongly and their emotions may run very high even if the new thing that happens is relatively minor.

Our emotions affect our actions. Without emotional regulation, intense emotions cause direct actions – there is no ‘brake’ between emotion and action to facilitate analysis of the situation and making rational decisions. The intensity of emotions also affects a person’s ability to make plans, carry out those plans or change them when needed.

Assignment: Take a moment to think about what your emotional reactions are like. You can write down your thoughts on a piece of paper or your phone. (Downloadable form at the bottom of the page.)

- Do you have strong emotional reactions, even to small things? What kind of things?

- Are you sometimes surprised by the intensity of your own emotions? How?

- Do you sometimes get stuck in a strong emotion for a really long time? What happens in those situations?

- Do strong emotions cause you to do things that you regret later? What kinds of things have you done?

Regulating strong and unpleasant emotions can be a challenge for anyone. Emotional regulation skills, which are needed to cope with these emotions, are learned in childhood and youth. Sometimes a person’s growth environment does not adequately support the development of their emotional regulation skills, leaving the person with inadequate or even harmful emotional regulation methods.

The person may fluctuate between over-controlling and under-controlling their emotions. Over-controlling means that they barely express their emotions and bottle them up, while under-controlling means that they have intense and uncontrollable bursts of emotion. In between these two extremes, the person lacks ways to directly express their emotions.

Recurring strong expressions of emotion can make others feel that they have to walk on eggshells in anticipation of potential bursts of anger. On the other hand, if a person completely refrains from communicating their emotions, others may become frustrated. The reactions of other people can cause a person struggling with emotional regulation to feel that there is something wrong with them. They may start to feel guilt or shame over their own emotions, or their emotions may even feel frightening to them.

If a person repeatedly experiences negative consequences from expressing or experiencing emotions – e.g. being left alone, feeling that they are not being heard or understood, or others being irritated – it is no wonder that they start to avoid their emotions. This may cause constant feelings of numbness, hollowness or emptiness.

If a person avoids their own emotions, they do not learn to understand and tolerate them. They may have difficulties with recognising and naming what emotions they are feeling. On the other hand, they may find it difficult to trust that their emotions will not have any negative consequences and understand what their emotions are trying to tell them.

One harmful way of coping with emotions that feel alien, strange and frightening is to start downplaying their significance and invalidating one’s own feelings. The person may have thoughts such as “I must not feel this way” or “it’s stupid to feel this way.” Because emotions cannot be chosen or eliminated, the person will experience a constant conflict that may cause them to feel worthless or very vulnerable.

Learning emotional regulation skills, familiarising yourself with your own emotions, accepting your emotions and validating them will help you live in peace with them.

Luckily, you can learn to recognise and understand your emotions. Both are steps towards better emotional regulation.

Emotions live in the body

The body and the mind are inseparably connected, and emotions in particular are felt in both. As such, it is useful to learn to identify where your emotions live in your body. For example, people often describe anxiety as a feeling of pressure or weight in their chest, and many learn to recognise from a familiar bodily sensation that they are experiencing anxiety.

In particular, if you have not learned to identify your emotions, listening to your body can be a good way to start. Everyone is unique in how they feel their emotions, but certain emotions are very often associated with commonly shared bodily sensations. Examining those can be a good starting point for familiarising yourself with your own emotions.

Because emotions are so strongly bodily, things that affect your body can also affect your emotions. For example, physical activity, breathing exercises and using cold are based on this very principle: you can calm your emotions by calming your body. How we use our body – how we sit or stand, how we breathe – has an impact on what kind of emotions we experience.

Emotions steer and motivate our actions

We all share a biological basis for what emotions have developed for. One of the most important and useful functions of emotions is to get us to act.

All emotions involve an impulse to act; for example, the feeling of fear urges us to protect ourselves from a threat, while the feeling of joy motivates us to approach the source of joy. Particularly in situations that call for quick reactions, emotions are needed to steer our actions, as they prompt us to act quickly and automatically.

Conversely, when a situation involves an excessively strong emotion, acting on an emotional impulse is not useful. For example, if you are feeling irritated or frustrated, those emotions can make you snap at people or give them the silent treatment. A better course of action would be to pay attention to your emotions, accept that you are feeling irritated and frustrated in that moment and, for example, tell the other person calmly how you are feeling and do something that will calm you down.

You can learn to understand your own emotions when you pay attention to what kind of situations usually trigger certain emotions and what kind of impulses are usually involved.

The significance of emotions in communication

Emotions are like a language that plays a particularly important role in connecting and interacting with other people. Showing our emotions to others strengthens that connection or provides feedback, and by contrast, the emotions that are stirred up inside us tell us something about other people and situations.

A good example of how important emotions are in communication is the act of apologising. If someone has offended you and apologises to you without expressing a feeling of remorse, the apology appears insincere and is difficult to accept. Conversely, if the apology comes with a clear expression of remorse, it is much easier to accept.

Even difficult and unpleasant emotions can have something important to say. For example, a feeling of shame tells us that we may have broken the rules of the group, and expressing shame to the others tells them that we are ready to follow the group’s practices.

Primary and secondary emotions

Emotions give rise to more emotions. A primary emotion is the first emotional reaction to a situation, while a secondary emotion arises from it as if in a chain reaction.

If a friend fails to come to a scheduled meeting and does not tell you in advance, your primary emotions can be worry, sadness, surprise and disappointment, for example. Anyone could feel like that in a similar situation. In turn, your secondary emotions can be indignation and anger.

A secondary emotion can often conceal the primary emotion. In the example situation above, the feeling of anger is easier to face and express than the more vulnerable feeling of sadness or disappointment. We also often act on the secondary emotion – when angry, we snap at the friend instead of expressing our sadness or disappointment. Secondary emotions are learned, and their purpose is to shield us from the primary emotion.

You can and should practise identifying your primary emotions. Facing a primary emotion and approaching it with compassion and acceptance is a challenging but important emotional regulation skill.

Emotional regulation skills mean various ways to influence the intensity of your emotional state, your actions when experiencing an emotion and how you approach emotions. They are not about controlling, eliminating or denying emotions. The video below provides more information on emotional regulation.

Emotion regulation

There are many different emotional regulation skills. Some of the skills are the most useful when you want to relieve an intense emotional state, whole others increase your wellbeing in the long term. The list below features examples of emotional regulation skills.

Identifying emotions: what are you feeling when an emotion arises? In which part of your body are you feeling it? What is the name of the emotion?

Listening to emotions: why and in what kind of situations are different emotions triggered? What are the emotions trying to communicate about situations, other people and yourself?

Expressing emotions: how can you talk about your emotions honestly and directly? What kind of words are there for emotions? What kind of facial expressions and gestures can be used to express different emotions?

Accepting emotions: are all the different emotions allowed in life? Or are some emotions ‘forbidden?’ Is there room for even unpleasant emotions in your mind?

Riding out an emotion: feeling the emotion in your mind and body as it is, stopping to experience the emotion. The emotion is allowed to occur and can be felt in all of its pleasantness or unpleasantness. Making room for the emotion without reacting to it. The emotion is allowed to go. The emotion is allowed to rise and fall like a wave on a sea, and you are riding that wave, feeling the entire emotional reaction.

Validating emotions: taking your emotions and the emotions of others seriously. Having a compassionate and interested attitude towards emotions instead of becoming upset or downplaying them, for example.

Regulating emotional sensitivity: your lifestyle can affect how easily emotions are triggered. The regularity of your eating rhythm and the quality of your food, your sleep rhythm and sleep quality, exercise, taking care of your physical health and the amount of stress you experience are all factors affecting emotional sensitivity.

Calming down: how can you calm yourself when your emotions are running high? How can you increase feelings of calmness and relaxation in everyday life?

Fact checking: all emotions are real and there are no wrong emotions. However, emotions are not facts and excessively strong emotions often tend to change how we perceive situations. How can you accept an emotion while also checking whether the emotion corresponds with facts?

Acting differently from an emotional impulse: all emotions carry an impulse. Sometimes you have to act differently from what an emotion suggests, as the emotion can urge you to take a course of action that is unacceptable or goes against your own values. Acting on an unpleasant emotion can exacerbate it and make the situation worse.

Problem solving: difficult situations that give rise to strong emotions sometimes call for efficient problem solving. The aim of problem solving is to change the situation to make it less unpleasant to be in. Functional problem solving reinforces your sense of control. In what kind of situations would problem solving be appropriate?

Increasing pleasant emotions: doing things that give you joy and gratification on a regular basis will balance your emotions. Additionally, acting in accordance with your own values and working towards your own long-term goals – even in baby steps – will bring meaning and satisfaction to your life.

The list above may feel overwhelming – how could anyone master all these skills and always succeed in emotional regulation? When you have thoughts along those lines, you should keep in mind that no one is perfect, and the goal is not to have all the skills mentioned in use at all times. The list can also remind you that emotional regulation skills are not to be taken for granted, but you must and can practise them – and it is never too late to start.

You should select skills that are relevant to you and suitable for your own needs. For example, if you are not yet able to identify your own emotions, you may also not be able to check facts yet. In such a case, you should take your time to familiarise yourself with your emotions.

Each and every person needs emotional regulation skills. Luckily, they can be practised through means such as chain analysis, emotional exposure and mindfulness exercises. In the form below, there are examples of different anxiety regulation skills which work for other emotions aswell. On the second page, there is a table where you can start taking notes of the regulation skills that work for you.

Highly intense difficult emotions call for distress tolerance skills, or so-called crisis skills. Distress tolerance skills can enable you to slightly alleviate a highly intense emotional state and then regulate your emotions through other means and examine the situation calmly. The video below provides more information on distress tolerance skills.

What to do in a crisis?

Distress tolerance skills are a great help for many when they have to cope with difficult situations. However, these skills are not suitable for using as the only means of coping with anxiety and other difficult emotions, as there is a risk of the person learning to avoid their emotions with these methods. Distress tolerance skills are the most useful when used in the short term to alleviate a highly intense emotional state.

You should also combine different distress tolerance skills. Alleviating an emotional state is like walking down a flight of stairs. One skill helps you go down one step, another skill another step. Distress tolerance skills will not eliminate your anxiety entirely, but they will help you cope with difficult situations without harming yourself or others or inadvertently making the situation worse.

Because strong emotions make information processing more difficult, many distress tolerance skill are based on influencing your emotions through your body. For example, breathing exercises, using cold and intense physical activity work on this principle.

What methods do you have for coping with anxiety or other difficult emotions? You should write down these methods and practise them even when you are feeling neutral or good.

Watch the videos on distress tolerance skills below.

Use cold to relieve anxiety

Intense physical exercise

Intense emotions stir up a stress reaction in the body. Adrenaline and other stress hormones cause physical sensations. Intense physical exercise uses the adrenaline and helps to calm down the body. The exercises also cause intense sensations in the muscles which brings attention efficiently to the present moment. Any physical exercise works but you can try the two exercises below.